The UK's best designed railway stations

Railway stations are often imposing places, but it’s the details that make us fall in love with them. Here, Umbrella writers talk about the parts that other stations simply can’t reach.

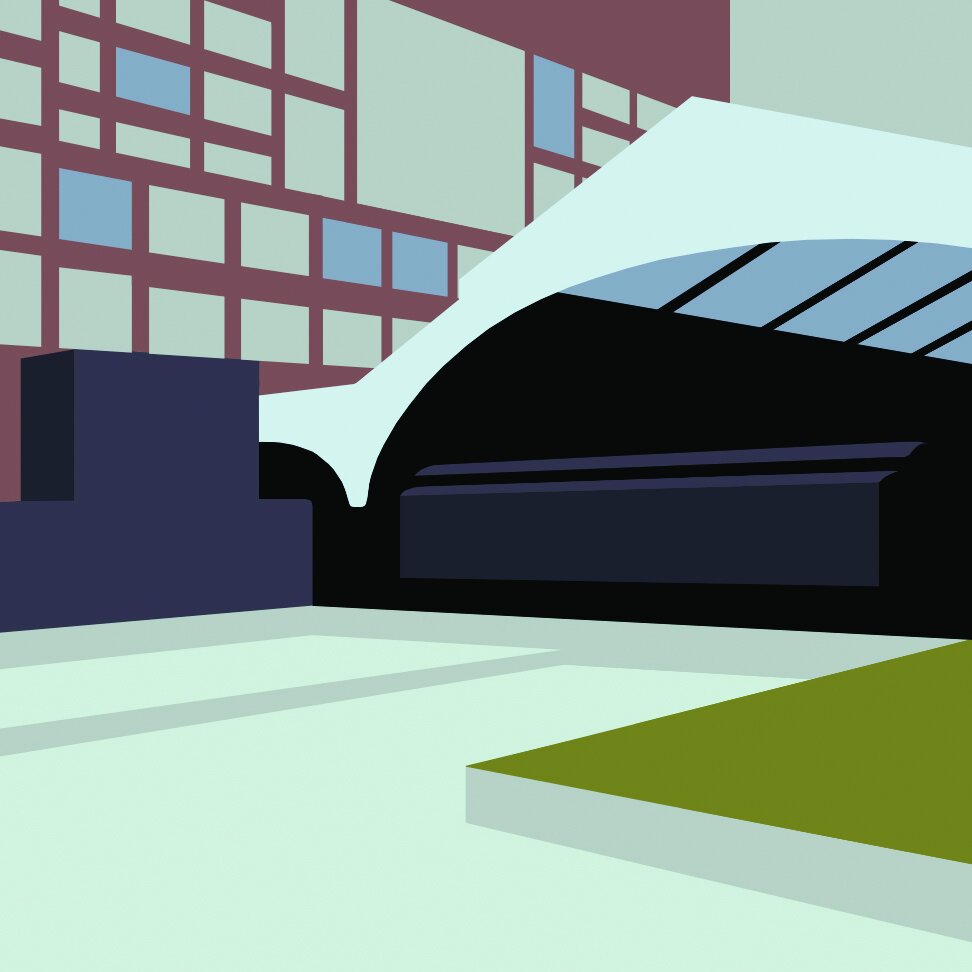

King’s Cross Square

If ever a station symbolised all that was wrong about ’60s and ’70s architecture it was King’s Cross. And specifically the green veranda built onto the entrance.

Today, everything has changed. King’s Cross, designed by Lewis Cubitt and opened in 1852, now has a beautiful, semi-circle extension to the side, while the veranda is no more, knocked down in 2012. In its place is King’s Cross Square.

With Cubitt’s minimalist masterpiece as its focus, KQS has become that most unusual thing in London: a shared space. Train staff puff on ciggies, commuters jump aboard buses and – on summer evenings – people gather to chat, eat and drink. Then when it goes dark, the spotlights come on and the station is lit up in all its austere magnificence. Anthony Teasdale

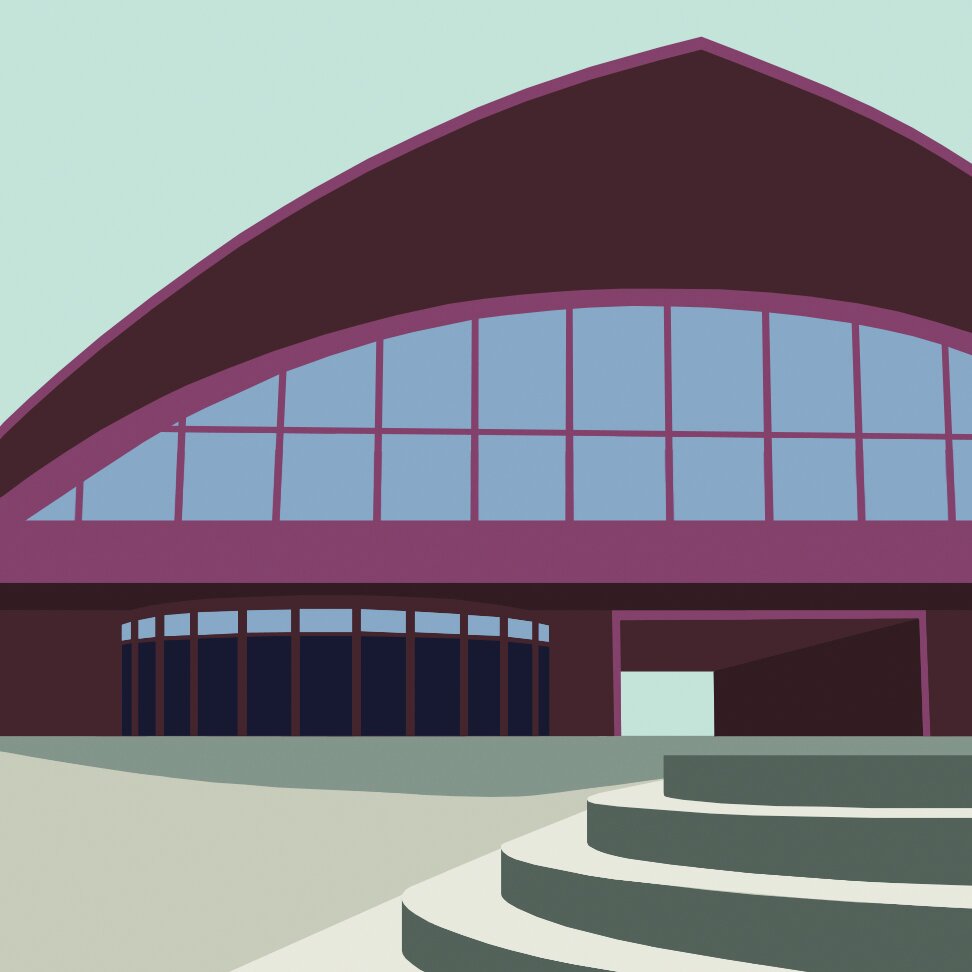

The sweeping roof curve, Newcastle

Railway victoriana is meant to be all soot-stained gothic with billowing smoke and steam asphyxiating the platforms. It’s a surprise, therefore, having traversed the Tyne from the south, to come across the airy, curving Grade 1-listed Newcastle Central Station, opened in 1850.

It is, in effect, a monumental neo-classical greenhouse composed of three pioneering arched train sheds painted white and cream to accentuate a surprisingly modern, airy sense of space. While it’s no Grand Central you’ll still find yourself gazing upwards at the serpentine, arched magnificence.

And the curve? All due to the East Coast Mainline, having crossed over the Tyne on Robert Stephenson’s High Level Bridge close to the station, needing to sweep round north again, and on towards Berwick and Scotland. John Mackin

Station Approach, Manchester Piccadilly

Ten years ago, at exactly 5pm on a Saturday, you’d find me dashing up Station Approach towards Piccadilly, protecting recently purchased records from the Manchester drizzle underneath the wavy modernist curve of Gateway House; a tired-looking ’60s throwback that was designed by the same architect behind London’s iconic Centrepoint tower.

Nicknamed the ‘lazy S’, Gateway House is currently undergoing a bit of a refurb and now even boasts a decent craft beer boozer. To most, station approach is just another way of getting from A to B. But to me, it was, and still is, the gateway to the bright excitement of my favourite city. Elliott Lewis-George

The Buffet Bar, Stalybridge

Recalling an age of British railways when waiting rooms were gas-lit and had roaring coal fires, this is a cosily perfect Edwardian pub. It’s won awards from CamRA and English Heritage – rightly so – and retains many of the original 1885 features.

A more recent extension included the 1st Class ladies waiting room complete with ornate ceiling and fascinating railway memorabilia.

If you’re up for it (and it always seems like a capital idea after a couple of foaming tankards) Stalybridge forms the starting point of the ‘Trans-Pennine Ale Trail’, stretching up the nine stations to Batley, all with a real ale pub either on the platform or immediately outside the station. A perfect outing. John Mackin

The North Concourse, Leeds station

Leeds station is an energy-sapping place. Travellers alighting are faced with a bewildering mix of platforms and stairwells (it’s England’s busiest station outside London), before exiting through a low-roofed concourse, home to the world’s most depressing WH Smith’s.

But take a turn left and you’re suddenly in a light, airy space decorated with art deco touches and filled with tasteful branches of high street shops. This is the Northern Concourse.

Originally a ticket hall, the concourse was part of the original Leeds City station, an amalgamation of New, and Wellington stations. Built in 1939, it connected the two termini.

When Leeds station was rebuilt (ie, ruined) in 1969, the Concourse decayed, but its recent refurbishment has brought back its modernist glory. Anthony Teasdale

Manchester Oxford Road

Being raised on a triangular patch of viaducts, Grade II-listed Oxford Road Station is what would have been created had a firm of Helsinki sauna designers been asked to make a model of Sydney Opera House.

What’s most striking is the extensive use of polished, laminated timber throughout. Timber was chosen as much for the fact that the station sits on weak Victorian viaducts as it was for the lobbying of the Timber Development Association in the late-’50s.

The result is one the most striking, unusual stations in Britain. Curling, distinctive overhanging canopies – 1960s modernism par excellence, except not executed in brutalist concrete – protect passengers from incessant Mancunian drizzle, while the façade beams out like a bishop’s mitre made of teak. John Mackin

The Tap pub at Sheffield

Enjoying a drink has always had a happy association with railway journeys. We all recognise the hiss of a tinny being opened (alongside those other BR staples – the ‘grab bag’ of Quavers and a copy of Viz). Yet most busy British railway stations are lacking somewhere decent to enjoy a pre-boarding pint on the concourse – which is what makes Sheffield so special.

Tucked away on platform one is The Sheffield Tap – an Edwardian railway diner reincarnated as a craft-beer paradise. With an on-site brewery and plenty of sensibly-priced ale, it’s long since become a destination in its own right for locals and travellers alike. It’s so wonderful, you might just ‘accidentally’ miss the 18.29 back to St Pancras. SImon Cunningham

The view over the city from Durham station

It comes as a joy to jaded travellers to come across the magnificent view of one of Europe’s best cityscapes. And it’s all included in the price of your ticket.

The small station itself is nothing special, but the part-Victorian, part-modern cantilevered platform roof offers splendid views over this ancient city. Just by gazing up from your phone, you can feast upon the World Heritage Site of the millennium-old Durham cathedral and the equally historic castle, which dominate and frame the skyline like two bookends.

Bill Bryson was fond of Durham, writing in Notes From A Small Island (1995): “Why, it’s a perfect little city. If you have never been to Durham, go there at once. Take my car. It’s wonderful.”

Ignore Bill – take the train instead. John Mackin

The façade at Huddersfield

You can tell a lot about a town by its train station. Some places regard themselves in modest terms – inconsequential stops on the line between grander, more important locations. The functional yet uninspiring architecture of their stations reflects this.

Other places, however, like to aim a little higher, declaring their position (or, as is often the case, the position they’d like to be in) with grand architectural statements.

Huddersfield in West Yorkshire is such a place. Situated between Leeds and Manchester, its station, opened in 1847, boasts as an incredible neoclassical exterior once described by poet John Betjeman as “the most splendid station facade in England”. If that’s not enough, there are two pubs either side of the entrance. Bravo. Matt Reynolds

Exchange Square, Liverpool Street

Located in the City of London (the financial quarter), Liverpool Street doesn’t make too much of an impression because it’s surrounded by streets and skyscrapers. Happily, that’s not the whole story. Take a walk behind the station and you’ll come upon one of the most striking open spaces in London: Exchange Square. Hemmed in by the terminus to the south and a monstrous office building to the north, Exchange Square is a place of reflection in an overwhelmingly urban environment.

Not only does it provide an incredible view of Liverpool Street station’s interior – check out the train shed’s arches – but the ‘Broadgate Venus’ statue on one side and the amphitheatre in the centre make it perfect for a post-work beer in the evening sun. Anthony Teasdale

The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway mosaic at Manchester Victoria

Built in 1844, in recent years Victoria has felt a little forlorn compared to Manchester’s other mainline station, Piccadilly. Unjustly so, as the former’s tile and brickwork knock the late-’60s shopping-centre chic of Piccadilly into a cocked hat, especially as Victoria has just had a £44m refurbishment.

The highlight of this work is not the vast glass roof but the tiled mosaic map that covers one wall opposite Platform 1. The piece shows all the lines of the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway which ran services in the north pre-British Rail, though with no sign of any competing lines, it’s less a map and more a piece of propaganda.

Today, the L&Y Railway is gone, and the only thing that remains is its beautiful map – oh, and the works football club. You’ll know them better as Manchester United. Anthony Teasdale

The roof at St Pancras

What was once an unused oddity, St Pancras’ 2007 refurbishment has made us fall in love again with this most theatrical of London stations.

While no one can deny the beauty of the fairytale-castle entrance, the station’s shining light is the roof of the train shed, designed by William Henry Barlow. When St Pancras’s modernisation was confirmed, engineers and architects pored over Barlow’s original drawings so they could reinstate its ‘ridge and furrow’ pattern.

The work didn’t stop there: the train shed’s cast iron supports were painted in the original shade of pale blue, while 160,000 pieces of Welsh slate joined the 18,000 panes of self cleaning glass to make up the roof. The result is the brightest station concourse in London. Anthony Teasdale

Illustrations by Joe Rampley